The Germans in England 1066-1598

THIS book must bear the stamp of a haste which only the urgency of war can justify. It was written in a few months in the intervals of my daily work, and if it has any merits, it is as a rough sketch and outline of its subject. As usual, I found the British Museum unfailing in its courtesy and in its resources. I have to thank Mr. Ferdinand de Mera for his invaluable assistance in translating German authorities and investigating crucial points in the Hanse Recesse and other German archives, and for his map of the roads, towns, and Kontors of the Hanseatic League. To Miss Thompson I am indebted for transcripts from Tudor manuscripts at the British Museum, to Mr. Claud Mullins for researches in the London Guildhall Library, and to Mr. J. S. Sandars for a revision of my proofs. The head of Queen Elizabeth, who expelled the Germans from England, was reproduced by the courtesy of the Medal Department of the British Museum.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I. "THE NATURAL ALLY"

II. THE PRICE OF A KING

III. SIMON DE MONTFORT

IV. THE HANSEATIC LEAGUE

V. THE CAMEL IN THE TENT

VI. THE HOUSE OF FAME BACK VIEW

VII. THE GERMANS RULE THE SEA

VIII. THE FIRST HAGUE CONVENTION

IX. THE MERCHANT ADVENTURERS

X. THE SACRED FRIENDSHIP

XI. WARWICK THE KING-MAKER

XII. "WE HAVE MADE AN END OF THE ENGLISH"

XIII. THE FIRST OF THE TUDORS

XIV. THE GERMANS MAKE AN ENEMY

XV. "A PURPOSED OVERTHROW"

XVI. ALLIANCE WITH RUSSIA

XVII. PHILIP AND MARY

XVIII. A GAME OF CHESS

XIX. CHECKMATE

CONCLUSION

APPENDICES

APPENDIX I. THE ANGEVTNS AND GERMANY

APPENDIX II. THE HANSE TOWNS

APPENDIX III. THE GERMAN SHARE IN ENGLISH TRADE AND PREFERENCE IN ENGLISH CUSTOMS

APPENDIX IV. THE AUGSBURG DECREE

APPENDIX V. SEBASTIAN CABOT

APPENDIX VI. THE "BAYE" IN HANSEATIC DOCUMENTS

AUTHORITIES

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

WHEN these present hostilities began, there was a prevailing belief that our relations with Germany had always been of the friendliest order, and many people were even surprised to find how bitterly the Germans hated England. Some of the newspapers described the naval engagement off Heligoland as our first fight with our "cousins" on the sea, and the German newspapers were full of talk about the Stammverwandt which we were said to have betrayed. And yet, as I have written this little book to show, our sailors were fighting the Germans all through the Middle Ages, and these sea-fights were not mere piracies and accidents, as some historians suppose, but the symptoms, as I might call them, of the long, fierce, and irregular conflict which was waged between Germany and England for sea-power and commercial supremacy.

Unless we understand this conflict, the history of England, from the time of the Angevins to the time of the Tudors, is mere sound and fury, signifying nothing. It is like a jigsaw puzzle which cannot be made into a picture because half the pieces are missing. But when we come to understand that the Germans were always interfering in English policy for their own ends, when we find them bribing a Chancellor, financing an invasion, and raising or pulling down a dynasty, then much that was formerly obscure becomes clear. We begin to see the hidden springs and inner motives of what was before a mere orgy of civil and foreign wars.

As I hope to show, there were two main motives of German interference in English policy, the one political and the other commercial. The main motive on the political side was to secure the assistance of England in the constant wars between France and the Empire, and also in the conflicts between the Empire and the Pope and between the Empire and Venice. Those wars with France, in which we reaped so much glory and shed so much blood for ends so barren and unprofitable, were fought less in our own interests than in the interests of Germany, which promoted and fomented them. The Germans came to look upon English assistance so much as a matter of course that when an English king was found who refused to assist them, an aggrieved King of the Romans set about to finance an English Pretender more amenable to German influence. Thus Perkin Warbeck wrote to the King of the Romans in January or February of 1496: “Were the Duke of York (i.e. Perkin) to obtain the Crown, the King of the Romans and the League (the Holy League) might avail themselves of England against the King of France as if the island were their own."

But we should not understand the political motive of German policy unless we realised the commercial motive. And here we come at once to that strange and obscure power in mediaeval Europe vaguely known to English readers as the Hanseatic League. Now I have seen it said that this League of cities was not native to Germany, but I do not think that this objection will be sustained upon a review of the evidence. The League certainly had its origin in Germany, and as certainly its ruling city was Lübeck. It was always the policy of the League to keep secret its extent and its membership; but of all the cities which are known to have belonged to the League, it is difficult to find one which could not be described as German. The stock exception is Dinant; but it is doubtful if Dinant was in the full sense a Hanseatic city. As will be seen from the notes on the point at the end of my book, there is evidence that Dinant was regarded by the cities as an outsider, and its share in Hanseatic privileges was probably given in order to obtain for Germany a port of entry into France. Bruges and Bergen were no more Hanseatic cities than London and Novgorod. They were Kontors or depots, the economic serfs and thralls of the League, without either membership or voice in its policy. The League had its house in these Kontor cities, and its council of merchants to do its business and represent its interests, just as England has its houses and its merchants in Hong-Kong; but just as Hong-Kong has no seat in our English Parliament, so Bruges had no place in the Hanse Day at Lübeck. The German "merchant" in Bruges might go to Lübeck as our Consul or the chairman of our Chamber of Commerce at Hong-Kong might come to London. He would be heard at the Day, and his opinion on Flemish policy would carry weight; but the town of Bruges itself, its mayor and its aldermen, had no place in the League: Bruges was a foreign city to be wheedled and bullied into subservience, but never to be admitted into partnership.

So with Novgorod, Bergen, Venice, Stockholm, London; the Germans were established more or less firmly in all these towns, and influenced to a greater or less degree their fortunes and their policy; but the towns themselves had no place in the League there was never any question of admitting them to membership. The case of the Polish towns is different. Dantzig was from the beginning in the inner circle, and enjoyed all the privileges of membership; but Dantzig was by nature and origin a Prussian city : its first Protector was the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, and it transferred its allegiance to Poland late in the day and for its own purposes: in all essentials it remained a Prussian city. And so with the other cities along the Baltic shore as far as Riga and Reval: they were in their origin German trading colonies, outposts of the League, and remained in policy and character foreign to their immediate surroundings. So we may suppose it was with Cracow, and possibly with those Saxon colonies which remain to this day in the south-east of Hungary, a foreign element in the Magyar State. They were the advance guards of a great commercial system which in substance as in origin was German.

And so if we go over the list of Hanseatic cities we shall find that almost all are German if indeed we can call the Prussian a German. What were the chief Hanseatic cities ? their names are sufficient answer: Lübeck, Dantzig, Bremen, Hamburg, Brunswick, Cologne. And we should find if we went more into detail that round Lübeck, Dantzig, Brunswick, and Cologne all the minor cities form themselves: they are the four "Thirds" into which the League for some purposes is divided.

The League, then, is accurately described as a federation of German cities. So it was understood in the Middle Ages. In the English charters its house in London is called "Gildhalla Teuton icorum"; and when the King of Poland sent an ambassador to London on behalf of the Hanse, Queen Elizabeth replied that if the League was not Prussian it was nothing.

"Men of the Emperor" and "Easterlings" are names which both described the German merchant before the Hanseatic League could be said to exist, and the two names possibly represented the two great divisions of German trade the Men of the Emperor being merchants of Cologne and of the Rhine, the Easterlings of Hamburg and the Baltic. However that may be, we shall find that Cologne was settled in England before Lübeck. Tradition dates the Guildhall of the Cologners in London from the Norman Conquest; but, as we shall see, there is evidence that the origin of those extraordinary privileges of the German merchant which are to be the staple of this little book is even further back in our history. The famous letter of Charlemagne to King Offa of Mercia amounts to a treaty of commerce on a basis of reciprocity: "You have also written to us about your merchants. We would have them enjoy our protection and defence within our realm . . . according to the ancient custom in commerce . . . . Show like favour to our merchants . . . ." On both sides the traders are to appeal to the justice of the country they are in. The significance of this letter to us is that Germany has something which is a necessity to England command of the pilgrim and trade road of the Rhine. Safe conduct on that road was in the hands of the Emperor, and, under the Emperor, of Cologne and the German princes. The Germans have always been a practical people, and it is not to be supposed that English pilgrims were allowed to use this road for nothing. Indeed our whole story teaches that when the German has something that the Englishman lacks, the Englishman has to pay a very heavy price for it.

But the Men of the Emperor and the Easterlings also commanded certain commodities of importance to England. The ancient exchange of Europe rested on the same basis as the exchange of China to-day weight of silver. The German pound-weight of silver was the standard for all Europe, and "pound sterling" is a corruption of "pound easterling." The ransom of Richard Coeur de Lion was estimated in the Cologne weight of silver, and the measure of Cologne was probably the measure of the Easterlings, the standard of all Germany. Now Germany set the standard in silver because Germany commanded the supply. The silver of "Beame," of which we hear so much in mediaeval trade, is silver from the mines of Bohemia.

But besides their command of silver, and therefore of exchange, and of trade routes, the Germans controlled sea-power outside the Mediterranean. And here we come to the secret of the power of the Baltic cities the head and centre of the Hanseatic League. Hemp for ropes, flax for sails, pitch for caulking and cordage, timber for masts, all these things came from the Baltic, and the cities which commanded these commodities commanded the sea. And if we add to these command of the Baltic corn-supply, command of the salt-fish trade, and the supply of wax, the necessities of light and religion, we shall be able to estimate the "pull" which the Baltic cities had over the rest of Europe in the Middle Ages.

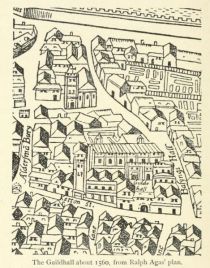

And Germans would not have been Germans if they had not got full value for all these advantages. There was, as we shall see, a time when the German cities could pass a law that English foreign trade was to be carried only in German ships, and this monopoly was at other times so well recognised that an English Government could forbid its subjects to engage in oversea trade. By skilful and usurious use of these manifold sources of power the Germans established themselves like a flourishing mistletoe in the clefts of our English apple-tree. The tale of their privileges is staggering to consider. They had their fortified Guildhall with its wharves and store-houses on the riverside; they were free of most, if not all, English taxes, both municipal and national, and paid less in customs than native Englishmen; they had not only their own court and aldermen for the government of their own affairs, but had special judges to settle their disputes with natives; they were above English juries and English law; they were exempt especially from that ancient custom of "hosting" which prevailed not only in England but throughout at least Northern Europe; they held their houses in London and other ports in freehold; they had control of one of the gates of the City of London, and were free to go out and in without paying municipal duties; they dealt not only "in gross" but in retail, in defiance of English custom.

They were thus favoured not only over other foreigners, but over Englishmen. Their advantage over other foreigners was so overwhelming that even the trade of the Venetians with England languished and dwindled almost to nothing, and their advantage over Englishmen was substantial enough to make the determination to end it one of the chief forces in our mediaeval politics. Here, then, we come to the main thread of our story the struggle between the German and the Englishman for English trade. This great struggle, which may be traced from the time of Henry III to the time of Elizabeth, seems to me one of the chief factors in our English history, and yet it has been almost ignored by our English historians. I do not know of a single English historian who has treated the subject as a connected whole. Welsford, over whose early death I shall never cease to mourn, touched upon it in that book of gold, The Strength of England, but did not fully realise its importance; Anderson, in his wonderful Origin of Commerce, which remains to this day our best economic history, tells the story on its commercial side with his accustomed erudition, but the political side is out of his sphere. The Germans understand its importance; but Lappenberg and Sartorius, the chief historians of the Hanseatic League in England, have not even been translated, and of those who deal with periods, like Schanz, Pauli, and Schulz, none, as far as I know, has been given to the English reader.

The cause of this neglect I do not trouble to investigate. Our English historians have been in general superior to trade; our economists superior to history. Some have marched triumphantly in the wake of our glorious campaigns in France, or those parts of them which are glorious; they have been so dazzled with the fair frontage of our Palace of Fame that they have not spared a glance for its kitchen premises; others have concerned themselves in our civil wars and our wars of union; and most have been preoccupied with certain specific factors in English history its constitutional and its religious quarrels. To me the one is the fine flower, the other the faint shadow of human affairs. I do not gather from his story that Simon de Montfort concerned himself much in the constitution of the English Parliament: his ends were more practical, he led the anti-foreign, and especially the anti-German, party in England. Matthew Paris understood this well enough, but the modern historian almost leaves it out of account. He learnedly discusses constitutional problems for which Simon probably cared little or nothing, and leaves unexplored the practical questions of protection and patriotism, for which Simon and his party cared a very great deal. And so down to the reign of Elizabeth. Froude has nothing to say of the Germans and whole volumes of the Spaniards. Yet our archives show clearly that the struggle with the Spaniard covered a deeper and more ancient conflict between the English and the German trader.

When even an English statesman can talk of trade as a sordid bond, it would be foolish to quarrel with English historians for leaving it out of account. And yet, as it seems to me, these trade relations with Germany must be understood if we are to understand our English history. I put the motives of man thus, in order of their strength: (1) Blood, that is race or nationality; (2) patriotism, or love of land and country; (3) interest, or the means by which man lives in trade and commerce; (4) religion, which is the hope and refectory of his soul, but as a motive uncertain and incalculable in its influence, and much used as a colour to disguise interest; and (5) politics, including all constitutional questions, which are merely the means or instruments for attaining these other ends. Now it is the proper business of the historian to understand all these motives and to explain their influence on events, for if the historian deals merely in events alone he signifies nothing. And yet if we read our English histories of the Wars of the Roses, it might be supposed that some at least of these motives were not then in operation. Events, in fact, are not so much explained as narrated. Let us, for example, take what is the crux and centre of these wars, the action of Warwick in transferring his allegiance from York to Lancaster, the flight and return of the King-Maker, the flight and return of Edward IV, and the Battle of Barnet in which Neville died. From the English historian we might suppose that Warwick was merely an unscrupulous noble, who acted through some pique or personal motive, ambition, or mere caprice. But if we apply our German key to these events, we find that Warwick fought Lübeck at sea; that Edward was made king on the "anti-German ticket"; that Edward, in the absence of Warwick, came to an understanding with the Hanse; that Warwick's invading army made an anti-German demonstration in London; that Edward fled to Flanders and returned in German ships; and that German influence was thrown into the scale for the defeat of Warwick, just as it had been used for the defeat of de Montfort. If English historians say little or nothing of all this, it is not forgotten by the German historians. Thus Pauli, for example: "When Edward IV was driven out they (the Hanseatic League) had to decide whether Henry VI should keep the throne or lose it again. . . . They helped the Germanic element to victory. If Henry VI had succeeded in retaining the Crown . . . the sea-power wielded by the German merchant would have gone to Rome . . . and the whole development of West European commerce would have been different. Thus the Germans freed themselves from a very serious danger, and at the same time forced the King under an obligation to the Hanse." *) In the opinion, then, of one of the greatest of German historians, at this crisis in English history an English king was a mere puppet in German hands, and the Wars of the Roses were part of the conflict for German commercial supremacy in England. And the contemporary Dantzig chronicler is just as explicit: "In the year 1469 there was great discord in England amongst the barons, one of the reasons being the (German) merchant." **) Here then is a motive for the Wars of the Roses, which puts all the chief actors in a new and surprising light. Warwick is a patriot who fights against the German domination on sea and land; Edward betrays the cause of English trade and shipping for German money; Warwick remains true to his principles and drives Edward from the Throne on which he had placed him; Edward is restored by the German power, and replaces the German merchant in his position of privilege.

*) Pauli, Die Hansestädte in den Rosenkriegen, p. 177.

**) Dantzig Chronicle to 1469, p. 5.

These motives being known, the Wars of the Roses no longer seem mere feudal anarchy, but take their place in English history as part of the great struggle for economic independence and sea-power, which is the substance of our narrative. As Simon de Montfort, so Warwick the King-Maker they were both national heroes who died fighting the Germans in the cause of protection. And just as the London merchant was defeated by the German merchant when the King of Germany restored Henry III to the throne, so the cause of English trade was laid in the dust when German ships carried Edward IV from Flanders to the port of Ravenspur. The restoration of Edward IV was followed by the most shameful treaty ever signed by an English king, I mean the Treaty of Utrecht." German power is more firmly established in England than ever," was the opinion of Lübeck. “We have made an end of the English," said the envoys of Dantzig. In the Treaty of Utrecht we have the spectacle of an English king, not only exempting German traders from all the customs paid by Englishmen, not only placing them above the justice of English courts, but making England the instrument for punishing the one German city which had deserted the Hanseatic League and espoused the cause of York. Cologne was deprived of all privileges in England until such time as the Hanseatic ban should be removed.

Henry VII, that wary and politic prince, did not dare to challenge directly the power of the German cities, although he must have been sorely tempted thereto by the intrigues of Germany against his throne. How far these intrigues were the work of the cities and how far the work of the German king, I have found it impossible to determine. But it is certain that the German traders in London were suspected of a connection with the Perkin Warbeck invasion, and Busch admits that they were probably the go-betweens. Maximilian's motive is plainly declared in his correspondence with Perkin, and in the despatches of the Venetian Ambassadors. He found Henry VII slack in the traditional English role of picking the German chestnut out of the French fire. But the cities also had a reasonable motive, for the Tudor policy was founded on the support of the English interest both in trade and manufacture. The English Parliament which welcomed the first Tudor to the throne marked its affection by granting the King a poll-tax on foreigners, and Henry's Navigation Acts, his encouragement of cloth manufacture, his charter to the Merchant Adventurers, and his alliance with Denmark were all indirect blows at the Hanseatic League. Yet the state of English shipping and the insecurity of his throne forbade him to do more than lay the foundations of that great national policy which in the hands of Elizabeth was to shatter in pieces the German power.

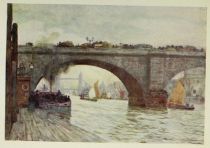

London, ab Arch of London Bridge

London, Aufgang zur London Bridges von der Südseite

London, Buckingham Palace

London, Chaucers Tomb

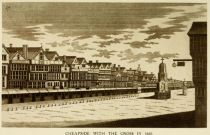

London, Cheapside with the Cross in 1660

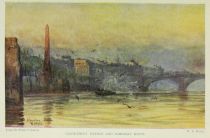

London, Cleopatras Needle and Sommerset House

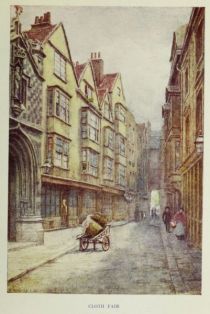

London, Cloth Fair

London, Clubs in Piccadilly

London, Deans Yard, Westminster

London, der Dom

London, der Strand 1616

London, die Bank, 1560

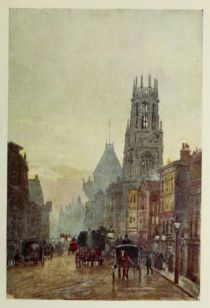

London, Fleet Street

London, Fountain Court and Middle Temple

London, Geschicklichkeitsspiele auf der Themse

London, Greenwich Palace from the Royal Dockyard at Deptfod in 1795

London, Grocers hall

London, Hafen um 1820

London, Hampstead in 1814

London, Handelshof um 1750

London, Hay Barges near Chelsea

London, Hendon

London, Henry VII. Chapel, Westminster Abbey

London, Highgate

London, Hochzeitsfeier in der Hansezeit

London, Hyde Park Corner From Rotten Row

London, Hyde Park Corner

London, in Golders Hill Park

London, Kleines Londoner Mädchen

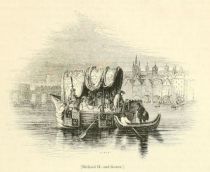

London, König Richard II. und der Poet Gower um 1380

London, Lambeth Palace in 1647+

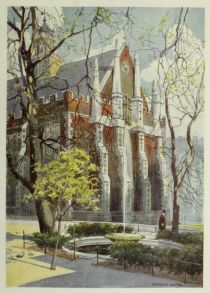

London, Lambeth Palace

London, Limehouse

London, London Bridge 1616

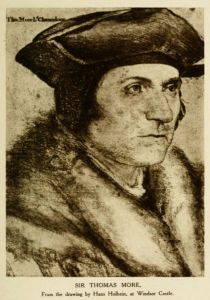

London, Morus, Thomas (1478-1535) englischer Staatsmann

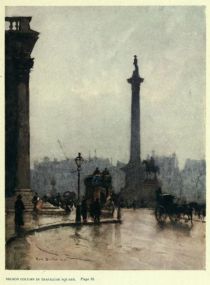

London, Nelson Column in Trafalgar Square

London, New River Head near Sadlers Wells in 1795

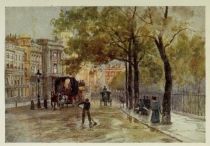

London, Northumberland Avenue

London, Old St. Pauls 1616

London, Palasthof um 1700

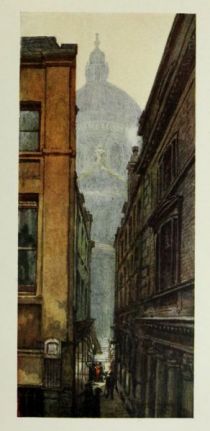

London, Pauls from the South End of Waterloo Bridge

London, Piccadilly Circus

London, Postkutsche um 1700

London, Rathaus, Gebäudekomplex

London, Richmond Bridge

London, Rotten Row (2)

London, Rotten Row

London, Schlosstreppe 1641

London, Sittenbild